Link goes to Course Miro Board

Catalogue Entry

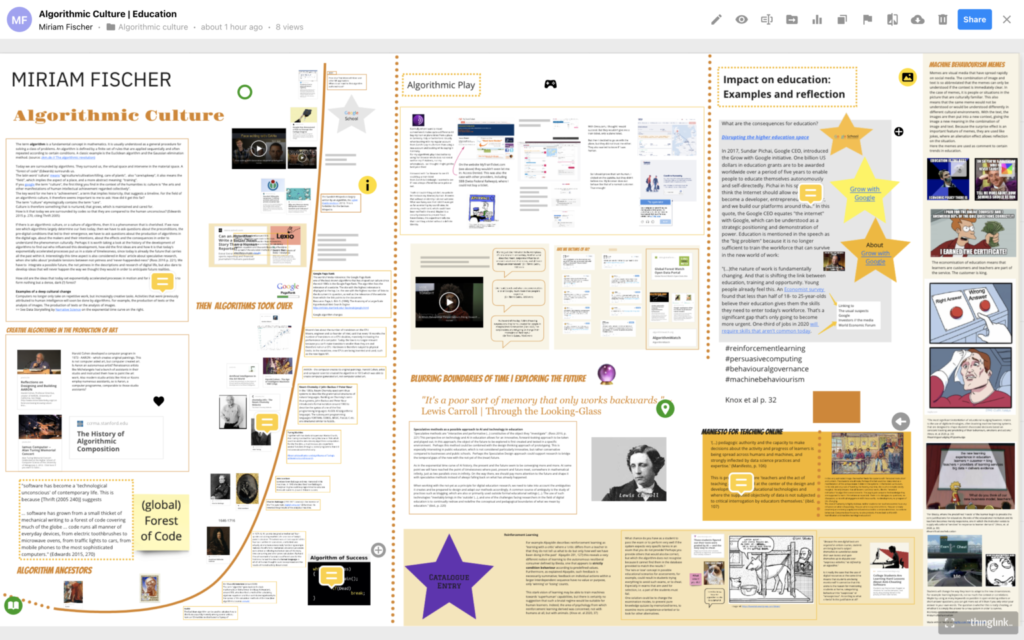

The Forest of Code

A culture is constituted by a complex conglomeration of social, historical, societal, individual, emotional, climatic, geographical, economic and political constellations. Certainly, the list of cultural components is not complete. To describe a culture of algorithms, we need to look at these layers that make up ‘culture’. In addressing a culture of algorithms in this digital exhibition, I have chosen a simplified historical component, which for me is always included when talking about culture, and which is one element in the ‘broader social systems in which [algorithms] operate’. (Manifesto 2020, p. 107). The image of being surrounded by algorithms, of their omnipresence, is also expressed in the metaphor of the “Forest of Code” (Edwards 2015), or in the comparison of algorithms with the new collective “unconscious” (ibid.). Both are powerful images that fit well with “culture”.

For me, an approach to a culture has a timeline. When something develops, there is a period or point in time in the past when it began, a spark that was carried on by people over time through narratives, feelings, science, politics, community. History means “looking into the past” – to understand the present and to see possible futures. Culture and history therefore belong together for me. The first part of the gallery is a very short abbreviated and absolutely arbitrary selection of people, events and inventions that have led to the current algorithmic state of the digital world. The curve is populated with only a few people and phenomena that impress me. The exponentiality of the curve expresses acceleration with which the latest developments manifest themselves and increasingly determine our lives. I find it fascinating that past, present and future almost come together in the highest level of exponentiality.

This is what I associate with speculative research methods (Ross 2016), which precisely try to bring the future into the present. Lewis Carroll takes up this tension with his statement ‘It’s a poor sort of memory that only works backwards.‘ (Thru the Looking Glass), especially since the word ‘memory’ clearly points to an individual or collective past, but he doubts this clear direction in time and thus suggests the possibility of a future in memory.

Algorithmic Play

In the middle part I deal with my algorithmic play, in which I tried to book a train journey from Zurich to Edinburgh without revealing my identity. I used the TOR browser to buy a ticket from various European train travel providers, but because I did not disclose my IP address, no one wanted to sell me a ticket. It was interesting to note, however, that I was not able to access all websites in the same way. On some of them I failed after the first click, while on others I got as far as the payment process. As a consequence, my venture is doomed to failure. I can’t buy a ticket unless I allow the algorithm to get information about me.

Powerful Google

Google is a guest in my gallery several times: on the one hand as Google School, a major player swan song of traditional education by Silicon Valley players (Weller 2015), and on the other hand as the scene of the scandal of a big company that fires recalcitrant employees from the ‘digital ethics’ department of all places.

Learnification of education

Finally, my exhibition is dedicated to the emergence of a new behaviourism in education through digital platforms with their immense collections of data, through the analysis of which certain behaviours of learners can be predicted and therefore also controlled (Knox et al. 2018). For this exhibition I have taken the liberty of presenting my insights anecdotally as memes, from pieces found on the net as well as from memes I have created myself. From my point of view, memes are quite an interesting format because they cannot be read without a common cultural background of the audience. The combination of image and very short text or slogan only works if the meaning of the image can be immediately culturally located, understood and the text interpreted. The text can also generate an intentional counterpoint to the image, which allows new perspectives on what is being addressed. For this reason they offer a good – and extremely short – analogy to the term ‘culture’.

References

Bayne, S., et al. (2020) The Manifesto for Teaching Online. Cambridge (MS), London: MIT

Carroll, L. (1994): Thru the Looking Glass. London New York: Penguin Popular Classics.

Edwards, R. Software and the hidden curriculum in digital education, Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 23:2, 265-279.

Knox, J. et al. (2018)

Ross, J. (2017) Speculative method in digital education research, Learning, Media and Technology, 42:2 p. 214-229.

Weller, M. (2015) MOOCs and The Silicon Valley Narrative. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2015(1): 5, p. 1-7.